Church, Blood, Bees, and Fighter-Jets

What should your home church have in common with a beehive, your circulatory system, and an aircraft carrier?

Watch the honeybees. They gather in their hive, each playing a role. There are worker bees, nurse bees, and house bees. From there, forager bees scatter on their mission—to collect the nectar that becomes honey.

In the circulatory system, your heart scatters blood all through your body, delivering oxygen and nutrients to keep you alive. The blood then returns, carrying carbon dioxide. While regathered in the lungs, the blood releases carbon dioxide and reloads with oxygen for your cells.

The planes land and gather on an aircraft carrier for refueling and repair. Mechanics, technicians, dentists, doctors, and cooks get pilots and planes ready to scatter again on their missions away from the warship.

So what should your church have in common with bees, blood, and fighter jets? Gathering and scattering. To carry out their work, they must all engage in this coming-and-going rhythm.

Shared Church: Two Modes

In the past, these shared-church blogs have focused on the need for participation when we gather as congregations. But the term, shared church, reaches even further than our Sunday assembling. Shared church also calls for the fruitful partnership between both modes of the church: church gathered and church scattered. Each must play its part. Each must support, strengthen, and depend on the other.

Hold on. . . doesn’t the Greek word usually translated as “church” refer to an assembly—a gathering? Yes. But the New Testament Christians did not spend 24/7 in their assemblies. In one of its modes, the church bunched up. In its other mode, the church spread out. For example, in Acts 8:1, when persecution struck the Jerusalem church, all its Christians (except the apostles) “were scattered throughout Judea and Samaria.” Did that church, when scattered, cease to exist as the church? Of course not.

Gathering-Scattering Rhythm

The God who made blood and bees to alternate between gathering and scattering also built that cadence into his church. God does not endorse “lone-ranger” faith. Unless we meet with other believers, we won’t last long. In a blog on beekeeping, the author says, “A single bee cannot survive on its own. It is helpful to view the hive as the organism and the individual bees as the cells, tissues, and organs that carry out the tasks needed to sustain the life of the colony as a whole.” Does your church operate as an organism and conduct itself as an earth-based colony of heaven?

On the other hand, no church can carry out God’s purposes in the world without scattering. Nor can any hive of bees. The nectar collected by the roaming foragers gets turned into honey and sealed into the honeycomb. This stored-up honey becomes the food supply for the winter months, when blossoms—the nectar wells—dry up. Beyond the hive, the honey blesses the world. Does your church give at least as much priority to its health and effectiveness in scattered mode as it does to its weekly gatherings?

Where is the Church on Monday?

Which brings up an important question: After the benediction on Sunday, your church scatters into what locations? Homes? Yes. Neighborhoods? Yes. But almost certainly the bulk of its non-gathered, prime-time hours will be spent in workplaces. The U. S. labor force includes virtually half the population. Come Monday, if those in your church reflect a similar cross-section of ages, every other person may well scatter into a business, a government agency, or some other workplace. Many will head off to do unpaid work.

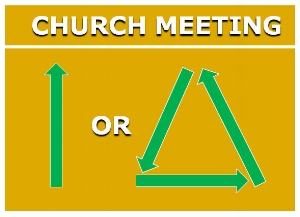

Over the course of a year, each of those Christians may spend between 75 and 200 hours in church gatherings—ten percent or far less of the 2,000 or so hours invested in working. Put graphically, that difference looks something like this:

Which Mode Gets Most Attention?

As I look back over decades of church involvement, it’s clear that we spend a great deal of time and effort on what happens when we gather. Planning the sequence of Sunday meetings. Writing and printing bulletins. Creating PowerPoint song and announcement slides. Practicing with praise bands or choirs. Preparing and preaching sermons. Organizing greeters and ushers. Arranging for small groups. And so on.

But it’s also obvious that we put little if any time into equipping Christians for their scattered-church roles—especially their working roles. Ask yourself these questions about your own church:

How are you equipping young people with biblical understanding about choosing their life’s work, in which they may invest 80- to 100,000 hours?

How are you helping those in non-church workplaces to identify and encourage fellow believers on the job?

How are you enabling employers and employees to recognize what is and is not appropriate in witnessing at work?

When was the last time, on a Sunday morning, you heard someone tell how God is moving in their workplace?

If your church experience is anything like mine, the answers to those questions are—well—embarrassing. “In the church,” writes John Mark Comer, in Garden City, “we often spend the majority of our time teaching people how to live the minority of their lives.” Could this help explain why the church has had so little influence on our outside-the-gathered-church culture?

Why Gather? Getting Set to Scatter

What do all the activities on board an aircraft carrier aim to accomplish? They prepare the pilots and planes for what they will do in the air, away from the gathering on the ship. In a similar way, what we do in our church gatherings should prepare us for what we will do outside the huddle. In another way, though, the aircraft carrier analogy doesn’t fit. Only a few on the ship serve as pilots who scatter. But in the church, everyone who gathers also scatters.

So in our one-anothering on Sundays, all of us should be helping to prepare each other for what we will be doing on weekdays. Shared church—at work in both its modes—is vital if we are to carry out God’s Kingdom purposes in his world.