Caring for Creation Calls for Shared Church

While hosting a webinar last week, I didn’t expect fresh insight into our need for shared church. But there it was—even though the online session focused on creation care.

What led to my role in this event? In June—because I teach the theology of work for the Bakke Graduate University—I plan to attend the Lausanne Global Workplace Forum (GWF) in Manila. Leading up to that gathering, ministry leaders have written some 30 “advance papers” on workplace-related subjects ranging from Arts in the Workplace to Women in Evangelism. To help participants prepare for the Manila conference, GWF is addressing many of these subjects in webinars called “Virtual Cafés.”

The Webinar on Creation Care

When asked to host one of these online discussions, I chose the session on creation care. Our main speaker, David Bookless, serves in the UK with A Rocha (Portuguese for “The Rock”), a group devoted to responsible stewardship of God’s earth. Ed Brown, the other speaker, serves as the Lausanne catalyst for creation care. Others joining our online session included Christians from Shanghai, West Africa, New Zealand, Brazil, and the U.S.

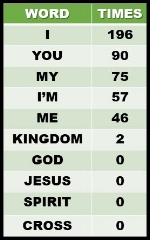

How did our conversation about creation care point to the need for shared church? As I listened to the speakers and guests, it hit me: I could not remember hearing anything in decades of church meetings about our tending the earth and its creatures. Nor could I recall, in my own 21 years of sermons, presenting even one message on that subject.

Why Have We Ignored Creation Care?

The church people I’ve spoken to all agree—we hear little or nothing on Sundays about our responsibility for the planet. Why? I suspect we can explain the silence from at least three angles.

First, we have reacted against a politicized and often God-evading environmentalism. The Lausanne advance paper, “Creation Care and the Workplace,” opens with these words: “When you hear the phrase ‘Creation Care and the Workplace,’ what comes to mind? Perhaps memos about turning off computers and office lights? Perhaps constraints on travel, resource-use, and waste? Perhaps a feeling that the ‘green police’ are the enemies of productivity and profit? It’s quite likely that there is a negative association: a sense that ‘creation care’ and ‘the workplace’ are somehow in opposition to each other.”

Second, countless Christians have been taught to think that God is going to toss this earth away—burn it to a crisp and start all over with a completely new earth. If true, then why spend any time or effort on a doomed planet? That would be like installing new kitchen cabinets in a house about to be bulldozed to make room for a city park.

Third, we still suffer from a centuries-old dualism—the unbiblical “sacred-secular divide.” In “My Pilgrimage in Theology,” N. T. Wright describes the change he underwent as he worked on his Colossians commentary: “Until then I had been basically, a dualist. The gospel belonged in one sphere, the world of creation and politics in another.” Dualism leads us to read verses like Colossians 3:2, “Set your minds on things above, not on earthly things,” as if God frowns on our thinking about clean air, over-fishing, or conservation . But this interpretation ignores the context, which deals with sins—sexual immorality, greed, filthy talk, lying, and the like.

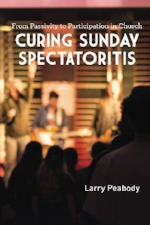

The Need for Participatory Church Meetings

One of our webinar guests has served as Chief Fisheries Manager in New Zealand. He told us: “I have felt that I’m working with God. But I am not sure that many have seen it like that.” Ed Brown added, “Christians who are scientists—especially those working in environmental fields—are some of the loneliest people I know.” Brown has heard Christians working in these areas say, “No one in my church understands me. They think I’m working for the devil.”

David Bookless has heard similar concerns: “Sadly there are many Christians who have been called by God into this area of creation care but have felt almost pushed to the margins by their churches. And in some cases, they have stopped attending.”

A young Brazilian woman, a geologist in an oil company, said: “Somehow I could not connect my faith with my vocation. I had never thought about creation care. It is not common in Brazil to talk about it in church. It would be great if we could share this vision with others in our church.”

As I listened, I thought: The congregations I’ve been a part of over the years have included many whose daily work involved direct care of the earth, its animals, and its plants. Christians in forest management. Those in departments of ecology. Farmers. Gardeners. Landscapers. Cattle ranchers. Loggers and tree trimmers. Oyster growers. And so on.

Suppose Christians doing such work were given opportunities to share about it in their church meetings. They could ask questions, offer experience-based insights, and explain what God has revealed to them about creation care. In other words, the wealth of understanding already deposited in members of Christ’s body, can strengthen the church in its role of caring for God’s earth.

God’s Earth is Groaning

Both Old and New Testaments make it clear that "The earth is the Lord's, and everything in it" (Ps. 24:1; I Cor. 10:26). And yet God’s earth is hurting: “the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time” (Rom. 8:22). Why? Because we humans, the property mangers God put in charge of his real estate, have done such a poor job of carrying out his First Commission, caring for the planet.

Isaiah saw this long ago. “The earth turns gaunt and gray, the world silent and sad, sky and land lifeless, colorless. Earth is polluted by its very own people, who have broken its laws, disrupted its order, violated the sacred and eternal covenant. Therefore a curse, like a cancer, ravages the earth. Its people pay the price of their sacrilege” (Is. 24:4-6, MSG).

As it groans, the earth is waiting and hoping for its property managers to do their job. Paul says the “creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the glorious freedom of the children of God” (Rom. 8:21).

In the Meantime, What Can We Do?

How can your church, through congregational participation, address caring for creation? Bookless said some churches hold an annual “Creation Fair Sunday.” During that time, they ask any whose work involves responsibility for the creation to come to the front for blessing and commissioning. Some churches invite local conservation, wildlife, environmental, or natural history groups to participate in the fair—even offering to pray for their work.

In the UK, Bookless told us, some churches have a slot called, “This Time Tomorrow.” In a five-or-ten-minute interview, someone tells what they will be doing this time tomorrow. This can cover the whole range of workplaces, he said, not just creation care.

Little did I know, when I agreed to host the webinar, that a subject like creation care would point to yet another reason for participatory church meetings!

To download the Lausanne Global Workplace Forum advance paper, “Creation Care,” click here.